- Markets Served

Automotive

Specialty

Illumination

Explore Our Lighting Solutions

- Products IlluminationAutomotiveMid-Power White LEDs

Mid-Power White LEDs

- LUXEON 2835 Architectural

- LUXEON 2835 Commercial

- LUXEON 2835 Commercial Deep Dimming

- LUXEON 2835 with CrispColor Technology

- LUXEON 2835 with FreshFocus Technology

- LUXEON 3014

- LUXEON 3014 with FreshFocus Technology

- LUXEON 3020

- LUXEON 3030 2D

- LUXEON 3030 2D Plus

- LUXEON 3030 HE

- LUXEON 3030 HE Plus

- LUXEON 3030 HE Plus Deep Dimming

- LUXEON 3030 HV

- LUXEON 3535L Line

Color LEDsHigh Power Color LEDs

- LUXEON C ES Color Line

- LUXEON C Color Line

- LUXEON CZ Color Line

- LUXEON Rubix

- LUXEON Z Color Line

- LUXEON Rebel Color Line

Mid Power Color LEDs

Multi-Color Packages

CoBsLUXEON Core Range CoBsHigh performance and reliability in standard footprint CoBs for new and existing designs.

- LUXEON CoB Core Range

- LUXEON CoB Core Pro

- LUXEON CoB Core Range PW

- LUXEON CoB Core Range – High Density Gen 2

LUXEON CS Range CoBsHigh performance and reliability in an industry-compatible, square footprint.

LUXEON CX Plus CoBsHigh performance and reliability in a CX-compatible footprint.

CoBs for Impactful Retail Lighting

- LUXEON CoB with CrispColor TechnologyMake colors pop and bring new life to fabrics with this high-gamut light source

- LUXEON CoB with FreshFocus TechnologyDeliver high-impact retail lighting with a precise color point and color stability for long-lasting results

Automotive Front SignalingSingle Die

Multi Die

LED Solutions & Modules

Automotive Rear SignalingLED Solutions & Modules

Automotive StylingLED Solutions

- Learn

- Tools & Support LED LightingAutomotive

- Company

Upcoming Events

August 4, 2021How do you farm in space?EventsJuly 28, 2021Ecodesign Directive. No Fear Here. -

- ×

Illumination

A comprehensive portfolio of application optimized LUXEON LEDs and the infinitely configurable Matrix Platform.

Explore illumination >Explore Our Lighting Solutions

Mid-Power White LEDs

- LUXEON 2835 Architectural

- LUXEON 2835 Commercial

- LUXEON 2835 Commercial Deep Dimming

- LUXEON 2835 with CrispColor Technology

- LUXEON 2835 with FreshFocus Technology

- LUXEON 3014

- LUXEON 3014 with FreshFocus Technology

- LUXEON 3020

- LUXEON 3030 2D

- LUXEON 3030 2D Plus

- LUXEON 3030 HE

- LUXEON 3030 HE Plus

- LUXEON 3030 HE Plus Deep Dimming

- LUXEON 3030 HV

- LUXEON 3535L Line

LUXEON 2835 ArchitecturalDesigned for architectural lighting solutions. High lumen output and efficacy. 1/9th micro bins 2, 3, 4, and 5-step SDCM, 3V, 6V, 9V options and full CCT and CRI options

LUXEON 2835 ArchitecturalDesigned for architectural lighting solutions. High lumen output and efficacy. 1/9th micro bins 2, 3, 4, and 5-step SDCM, 3V, 6V, 9V options and full CCT and CRI options

LUXEON 2835 CommercialDesigned to be the price/performance leader for commercial indoor lighting solutions when lumens per Watt and lumens per dollar are the driving metrics for development.

LUXEON 2835 CommercialDesigned to be the price/performance leader for commercial indoor lighting solutions when lumens per Watt and lumens per dollar are the driving metrics for development.

LUXEON 2835 Commercial Deep DimmingThe mid-power product with Deep Dimming capability ensures that your fixtures and installations remain uniform when dimming the current levels to 1% of the typical current or less.

LUXEON 2835 Commercial Deep DimmingThe mid-power product with Deep Dimming capability ensures that your fixtures and installations remain uniform when dimming the current levels to 1% of the typical current or less. LUXEON 2835 with CrispColor TechnologyThe perfect 2835 mid-power LED for fashion retail lighting highlighting rich color and increasing contrast. CrispColor technology brings fabrics and textures to life.

LUXEON 2835 with CrispColor TechnologyThe perfect 2835 mid-power LED for fashion retail lighting highlighting rich color and increasing contrast. CrispColor technology brings fabrics and textures to life.

LUXEON 2835 with FreshFocus TechnologyBring out reds for greater visual appeal to meat, or breads and pastries. Emphasizes the natural colors of fish and gives that “just picked” appearance to produce.

LUXEON 2835 with FreshFocus TechnologyBring out reds for greater visual appeal to meat, or breads and pastries. Emphasizes the natural colors of fish and gives that “just picked” appearance to produce.

LUXEON 3014Compact package: 3.0mm x 1.4mm x 0.7mm—is ideal for achieving uniform light output where space is limited. Hot-color targeted at a junction temperature of 65°C.

LUXEON 3014Compact package: 3.0mm x 1.4mm x 0.7mm—is ideal for achieving uniform light output where space is limited. Hot-color targeted at a junction temperature of 65°C.

LUXEON 3014 with FreshFocus TechnologyCompact package: 3.0mm x 1.4mm x 0.7mm. FreshFocus Technology spectrum highlights food items.

LUXEON 3014 with FreshFocus TechnologyCompact package: 3.0mm x 1.4mm x 0.7mm. FreshFocus Technology spectrum highlights food items.

LUXEON 3020Hot-color targeted EMC-based 3.0mm x 2.0mm QFN, delivers superior efficacy, lumen maintenance, and assurance of ANSI color compliance at operating conditions — 85°C.

LUXEON 3020Hot-color targeted EMC-based 3.0mm x 2.0mm QFN, delivers superior efficacy, lumen maintenance, and assurance of ANSI color compliance at operating conditions — 85°C.

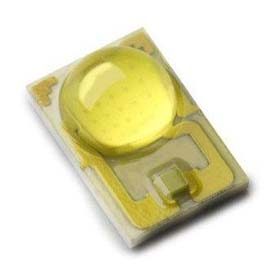

LUXEON 3030 2DThis high flux, hot-color targeted to ensure color performance at application conditions—85°C. 65mA and 120mA, 6V surface-mount emitter solution.

LUXEON 3030 2DThis high flux, hot-color targeted to ensure color performance at application conditions—85°C. 65mA and 120mA, 6V surface-mount emitter solution. LUXEON 3030 2D PlusExceptional luminous efficacy and cost efficiency within a robust 3030 6V package, and designed for outdoor and industrial lighting applications.

LUXEON 3030 2D PlusExceptional luminous efficacy and cost efficiency within a robust 3030 6V package, and designed for outdoor and industrial lighting applications. LUXEON 3030 HEThis go to 3030 mid-power package delivers high value flux and efficacy with proven longevity and robustness.

LUXEON 3030 HEThis go to 3030 mid-power package delivers high value flux and efficacy with proven longevity and robustness.

LUXEON 3030 HE PlusThe most powerful and robust 3030 mid power LED available today.

LUXEON 3030 HE PlusThe most powerful and robust 3030 mid power LED available today. LUXEON 3030 HE Plus Deep DimmingFor dimming applications that require extremely uniform light output while dimming. Top notch lm/W performance, lifetime, and pure 3 SDCM color bin with 0.1 Vf width.

LUXEON 3030 HE Plus Deep DimmingFor dimming applications that require extremely uniform light output while dimming. Top notch lm/W performance, lifetime, and pure 3 SDCM color bin with 0.1 Vf width.

LUXEON 3030 HVHigh voltage, low current package compatible with more efficient and cost effective drivers. 1/9th micro-color binned for tight color control and hot-color targeted - 85°C.

LUXEON 3030 HVHigh voltage, low current package compatible with more efficient and cost effective drivers. 1/9th micro-color binned for tight color control and hot-color targeted - 85°C.

LUXEON 3535L LineBroad flux and efficacy combinations and with full CCT and CRI options and a max drive of 200mA. Supports EnergyStar and DLC. 1/7th ANSI color binning delivers tight color control.

LUXEON 3535L LineBroad flux and efficacy combinations and with full CCT and CRI options and a max drive of 200mA. Supports EnergyStar and DLC. 1/7th ANSI color binning delivers tight color control.

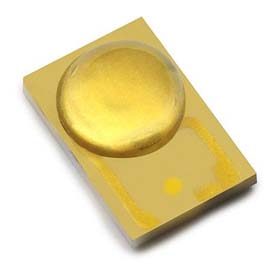

LUXEON HL1ZOffers high flux density performance in a compact footprint, enabling elegant and superior luminaire designs

LUXEON HL1ZOffers high flux density performance in a compact footprint, enabling elegant and superior luminaire designs LUXEON RebelProven reliable, 4530 high-power LED that gives you the design flexibility and performance you need

LUXEON RebelProven reliable, 4530 high-power LED that gives you the design flexibility and performance you need LUXEON Rebel PLUSProven reliable, hot-tested at 85C, this 4530 high-power LED offers color consistency at 80CRI for a range of CCTs.

LUXEON Rebel PLUSProven reliable, hot-tested at 85C, this 4530 high-power LED offers color consistency at 80CRI for a range of CCTs. LUXEON ZAt 1.3mm x 1.7mm, it is perfect for use in close-packed applications requiring an undomed solution. Performance specified at 500mA and Tj=85°C

LUXEON ZAt 1.3mm x 1.7mm, it is perfect for use in close-packed applications requiring an undomed solution. Performance specified at 500mA and Tj=85°C LUXEON ZAt 1.3mm x 1.7mm, it is perfect for use in close-packed applications requiring an undomed solution. Performance specified at 500mA and Tj=85°C

LUXEON ZAt 1.3mm x 1.7mm, it is perfect for use in close-packed applications requiring an undomed solution. Performance specified at 500mA and Tj=85°C LUXEON ZAt 1.3mm x 1.7mm, it is perfect for use in close-packed applications requiring an undomed solution. Performance specified at 500mA and Tj=85°C

LUXEON ZAt 1.3mm x 1.7mm, it is perfect for use in close-packed applications requiring an undomed solution. Performance specified at 500mA and Tj=85°C LUXEON HL2XThis high-power, domed emitter for outdoor and industrial applications. Standard 3535 package with 3-stripe footprint delivers superior output, efficacy, and color stability.

LUXEON HL2XThis high-power, domed emitter for outdoor and industrial applications. Standard 3535 package with 3-stripe footprint delivers superior output, efficacy, and color stability. LUXEON HL2Z2mm square CSP-based, high power, un-domed emitter designed to provide leading flux density, superior color consistency, high luminance, and extreme flexibility in lighting solutions.

LUXEON HL2Z2mm square CSP-based, high power, un-domed emitter designed to provide leading flux density, superior color consistency, high luminance, and extreme flexibility in lighting solutions. LUXEON Rebel ESTested and binned at 700mA, this high-power package is more efficient for 4100K and 5650K applications.

LUXEON Rebel ESTested and binned at 700mA, this high-power package is more efficient for 4100K and 5650K applications. LUXEON Z ESExtreme flux density in a micro footprint package for precise optical control. Product performance at 700mA and 350mA, Tj=85°C.

LUXEON Z ESExtreme flux density in a micro footprint package for precise optical control. Product performance at 700mA and 350mA, Tj=85°C. LUXEON TXSpecified, targeted and tested hot, at 85°C, to ensure in-application performance. 3 and 5 Step Freedom from Binning , 70, 80 and 90 CRI. Max current of 1.5A.

LUXEON TXSpecified, targeted and tested hot, at 85°C, to ensure in-application performance. 3 and 5 Step Freedom from Binning , 70, 80 and 90 CRI. Max current of 1.5A. LUXEON TXSpecified, targeted and tested hot, at 85°C, to ensure in-application performance. 3 and 5 Step Freedom from Binning , 70, 80 and 90 CRI. Max current of 1.5A.

LUXEON TXSpecified, targeted and tested hot, at 85°C, to ensure in-application performance. 3 and 5 Step Freedom from Binning , 70, 80 and 90 CRI. Max current of 1.5A. LUXEON HL4XA high-power directional emitter designed for outdoor and industrial applications with maximized lumen output and ability to sustain maximum drive current at 4A.

LUXEON HL4XA high-power directional emitter designed for outdoor and industrial applications with maximized lumen output and ability to sustain maximum drive current at 4A. LUXEON HL4ZA high-power, high-luminance emitter that delivers industry leading efficacy of 157lm/W and lumen output 635lm (typical) from a 2.16mmx2.16mm light emitting surface in a standard 3535 undomed package.

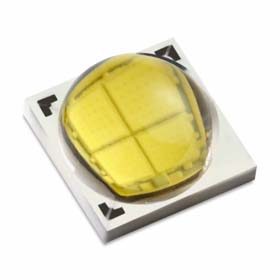

LUXEON HL4ZA high-power, high-luminance emitter that delivers industry leading efficacy of 157lm/W and lumen output 635lm (typical) from a 2.16mmx2.16mm light emitting surface in a standard 3535 undomed package. LUXEON 5050Multi-die high power package is extremely robust with efficacy exceeding 200 lm/W. 70-80-90 CRI, hot color targeted and available in Round (6V, 24V), Square (6V, 30V), HE (6V, 24V) and HE Plus (6V) versions with small LES.

LUXEON 5050Multi-die high power package is extremely robust with efficacy exceeding 200 lm/W. 70-80-90 CRI, hot color targeted and available in Round (6V, 24V), Square (6V, 30V), HE (6V, 24V) and HE Plus (6V) versions with small LES. LUXEON V4mm x 4mm footprint offers unique combination of high efficacy at high drive current with very low thermal resistance. Product performance at 1400mA, Tj=85°C

LUXEON V4mm x 4mm footprint offers unique combination of high efficacy at high drive current with very low thermal resistance. Product performance at 1400mA, Tj=85°C LUXEON V4mm x 4mm footprint offers unique combination of high efficacy at high drive current with very low thermal resistance. Product performance at 1400mA, Tj=85°C

LUXEON V4mm x 4mm footprint offers unique combination of high efficacy at high drive current with very low thermal resistance. Product performance at 1400mA, Tj=85°C LUXEON HL4XA high-power directional emitter designed for outdoor and industrial applications with maximized lumen output and ability to sustain maximum drive current at 4A.

LUXEON HL4XA high-power directional emitter designed for outdoor and industrial applications with maximized lumen output and ability to sustain maximum drive current at 4A. LUXEON MHigh flux density from a 3mm2 area enables reduced emitter count and compact fixture design. 12V and 6V options with 3 or 5 Step SDCM and 70-80-90CRI.

LUXEON MHigh flux density from a 3mm2 area enables reduced emitter count and compact fixture design. 12V and 6V options with 3 or 5 Step SDCM and 70-80-90CRI. LUXEON MXDelivers efficacy up to 157 lm/W and optically compatible with LUXEON M. Product performance at 700mA and 1400mA, Tj=85°C. 70-80-90CRI, 6V and 12V.

LUXEON MXDelivers efficacy up to 157 lm/W and optically compatible with LUXEON M. Product performance at 700mA and 1400mA, Tj=85°C. 70-80-90CRI, 6V and 12V. LUXEON MZUndomed for tighter beam control and higher punch with identical solder footprint to LUXEON M. Product performance at 700mA and 1400mA, Tj=85°C. 70-80-90CRI, 3V, 6V and 12V.

LUXEON MZUndomed for tighter beam control and higher punch with identical solder footprint to LUXEON M. Product performance at 700mA and 1400mA, Tj=85°C. 70-80-90CRI, 3V, 6V and 12V. LUXEON 7070Exceptionally robust with output >1400lm and efficacy > 180 lm/W. Hot tested, 70-80-90CRI and a full range of CCTs. Performance at 700mA, Tj=25°C Flux and Tj=85°C for R9 and CRI

LUXEON 7070Exceptionally robust with output >1400lm and efficacy > 180 lm/W. Hot tested, 70-80-90CRI and a full range of CCTs. Performance at 700mA, Tj=25°C Flux and Tj=85°C for R9 and CRI

High Power Color LEDs

- LUXEON C ES Color Line

- LUXEON C Color Line

- LUXEON CZ Color Line

- LUXEON Rubix

- LUXEON Z Color Line

- LUXEON Rebel Color Line

Mid Power Color LEDs

Multi-Color Packages

LUXEON C ES Color LineDesign powerful, complex multi-color arrays with minimal LED-to-LED spacing

LUXEON C ES Color LineDesign powerful, complex multi-color arrays with minimal LED-to-LED spacing LUXEON C Color LineDesigned for flawless color mixing with a single focal length. 13 colors plus white CCTs 2200K to 5700K and 70 to 90 CRI.

LUXEON C Color LineDesigned for flawless color mixing with a single focal length. 13 colors plus white CCTs 2200K to 5700K and 70 to 90 CRI. LUXEON CZ Color LineUndomed 2.0mm x 2.0mm package for maximum flexibility and color mixing . 13 colors plus white CCTs 2200K to 5700K and 70 to 90 CRI.

LUXEON CZ Color LineUndomed 2.0mm x 2.0mm package for maximum flexibility and color mixing . 13 colors plus white CCTs 2200K to 5700K and 70 to 90 CRI. LUXEON RubixHigh drive, up to 3A, in a tiny, undomed 1414 package is the ultimate choice for flexibility and punch in color applications. 7 different colors plus white.

LUXEON RubixHigh drive, up to 3A, in a tiny, undomed 1414 package is the ultimate choice for flexibility and punch in color applications. 7 different colors plus white. LUXEON Z Color Line2.2mm2, undomed compact design. 10 colors from deep red to royal blue. Performance tested at 500mA,Tj=25°C and Tj=85°C

LUXEON Z Color Line2.2mm2, undomed compact design. 10 colors from deep red to royal blue. Performance tested at 500mA,Tj=25°C and Tj=85°C

LUXEON Rebel Color LineIdeal for a wide variety of lighting, signaling, signage, and entertainment applications. 11 colors in a proven 350mA package.

LUXEON Rebel Color LineIdeal for a wide variety of lighting, signaling, signage, and entertainment applications. 11 colors in a proven 350mA package. LUXEON 3535L Color LineSeven colors in a standard 3535 package tested at 100mA, Tj=25°C. Same focal length as LUXEON Rebel and LUXEON Z.

LUXEON 3535L Color LineSeven colors in a standard 3535 package tested at 100mA, Tj=25°C. Same focal length as LUXEON Rebel and LUXEON Z. LUXEON 2835 Color Line13 colors plus 3 whites in an efficient 2835 mid-power package. Perfect for a wide range of indoor and outdoor applications.

LUXEON 2835 Color Line13 colors plus 3 whites in an efficient 2835 mid-power package. Perfect for a wide range of indoor and outdoor applications. LUXEON 3528This slim package is only 1.75mm high, can manage 0.5W of power, and has an IPX8 water resistance rating. The white package is suitable for indoor and outdoor applications.

LUXEON 3528This slim package is only 1.75mm high, can manage 0.5W of power, and has an IPX8 water resistance rating. The white package is suitable for indoor and outdoor applications. LUXEON 5052 RGBWMake color tuning easier with this 4-in-1 RGBW package. Choose Blue or Royal Blue and a white with CCT from 2200K to 6500K. Product performance tested at 120mA,Tj=25°C.

LUXEON 5052 RGBWMake color tuning easier with this 4-in-1 RGBW package. Choose Blue or Royal Blue and a white with CCT from 2200K to 6500K. Product performance tested at 120mA,Tj=25°C.

LUXEON SunPlus 20 LineThe 2.0mm2 package is available in Far Red, Deep Red, Royal Blue, Lime, and Cool White with viewing angles of 120° and 150°. Product performance is at 350mA, Tj=85°C.

LUXEON SunPlus 20 LineThe 2.0mm2 package is available in Far Red, Deep Red, Royal Blue, Lime, and Cool White with viewing angles of 120° and 150°. Product performance is at 350mA, Tj=85°C. LUXEON SunPlus 2835 LineBinned and tested based on Photosynthetic Photon Flux (PPF) color options include Purple (2.5% to 25% Blue), Horticulture White, Far Red, Deep Red, Royal Blue, and Lime.

LUXEON SunPlus 2835 LineBinned and tested based on Photosynthetic Photon Flux (PPF) color options include Purple (2.5% to 25% Blue), Horticulture White, Far Red, Deep Red, Royal Blue, and Lime. LUXEON SunPlus 35 LineBinned and tested based on Photosynthetic Photon Flux (PPF) color options include Purple (2.5% to 25% Blue), and Lime. Product performance is at 100mA, Tj=25°C.

LUXEON SunPlus 35 LineBinned and tested based on Photosynthetic Photon Flux (PPF) color options include Purple (2.5% to 25% Blue), and Lime. Product performance is at 100mA, Tj=25°C. LUXEON SunPlus CoB LineLUXEON SunPlus CoB Line includes three different LES sizes: 15mm, 19mm, and 32mm. Available in Purple (12.5% Blue) and Rose. Typ. PPF (

LUXEON SunPlus CoB LineLUXEON SunPlus CoB Line includes three different LES sizes: 15mm, 19mm, and 32mm. Available in Purple (12.5% Blue) and Rose. Typ. PPF (μmol/s) in PAR (400 to 700nm) is 53 to 200.  LUXEON SunPlus HPEWith an industry-standard footprint of 3.5mm x 3.5mm, LUXEON SunPlus HPE is a deep red High Power LED with a peak wavelength of 660nm, the best in class performance and efficacy for horticulture applications.

LUXEON SunPlus HPEWith an industry-standard footprint of 3.5mm x 3.5mm, LUXEON SunPlus HPE is a deep red High Power LED with a peak wavelength of 660nm, the best in class performance and efficacy for horticulture applications. LUXEON SunPlus 3030Widely available, this top performing broad-spectrum white light delivers top rated μmol/J and PPF (μmol/s) performance and long lifetime with CCTs ranging from 2200K to 6500K.

LUXEON SunPlus 3030Widely available, this top performing broad-spectrum white light delivers top rated μmol/J and PPF (μmol/s) performance and long lifetime with CCTs ranging from 2200K to 6500K. LUXEON SunPlus 5050Four versions, Round, Square, HE and HE Plus, 6-30V options, and a package designed for harsh environments make this a perfect choice for horticulture applications.

LUXEON SunPlus 5050Four versions, Round, Square, HE and HE Plus, 6-30V options, and a package designed for harsh environments make this a perfect choice for horticulture applications.

LUXEON Core Range CoBsHigh performance and reliability in standard footprint CoBs for new and existing designs.

- LUXEON CoB Core Range

- LUXEON CoB Core Pro

- LUXEON CoB Core Range PW

- LUXEON CoB Core Range – High Density Gen 2

LUXEON CS Range CoBsHigh performance and reliability in an industry-compatible, square footprint.

LUXEON CX Plus CoBsHigh performance and reliability in a CX-compatible footprint.

CoBs for Impactful Retail Lighting

- LUXEON CoB with CrispColor TechnologyMake colors pop and bring new life to fabrics with this high-gamut light source

- LUXEON CoB with FreshFocus TechnologyDeliver high-impact retail lighting with a precise color point and color stability for long-lasting results

LUXEON CoB Core Range8 different LES sizes from 6 to 32mm. 2200K to 5600K CCT, 70 to 90 CRI. Efficacy > 160lm/W. Reliable and efficient options for the widest range of applications.

LUXEON CoB Core Range8 different LES sizes from 6 to 32mm. 2200K to 5600K CCT, 70 to 90 CRI. Efficacy > 160lm/W. Reliable and efficient options for the widest range of applications. LUXEON CoB Core ProLES sizes of 9, 13, 15 and 19 at 3000K make for a very high efficacy and excellent quality of light option that makes colors pop.

LUXEON CoB Core ProLES sizes of 9, 13, 15 and 19 at 3000K make for a very high efficacy and excellent quality of light option that makes colors pop. LUXEON CoB Core Range PWBuilt for applications that need the highest quality of light combined with market leading performances. Beautiful color transforms areas into vibrant spaces. LES from 9 to 19mm.

LUXEON CoB Core Range PWBuilt for applications that need the highest quality of light combined with market leading performances. Beautiful color transforms areas into vibrant spaces. LES from 9 to 19mm.

LUXEON CoB Core Range High DensityDouble the flux in the same form factor. Focus on achieving the highest Center Beam Candle Power. 6, 9, and 11mm LES and a flux range as high as 8,000 lumens

LUXEON CoB Core Range High DensityDouble the flux in the same form factor. Focus on achieving the highest Center Beam Candle Power. 6, 9, and 11mm LES and a flux range as high as 8,000 lumens LUXEON CS CoBIndustry standard square footprint enables easy design-in for new luminaire programs and a cost-effective replacement for existing solutions where an upgrade is desired.

LUXEON CS CoBIndustry standard square footprint enables easy design-in for new luminaire programs and a cost-effective replacement for existing solutions where an upgrade is desired. LUXEON CS Pro CoBWith spectra tailored to retail lighting, the CS Pro CoBs are easy to design-in and are a cost-effective replacement for solutions where superior quality of white light is required

LUXEON CS Pro CoBWith spectra tailored to retail lighting, the CS Pro CoBs are easy to design-in and are a cost-effective replacement for solutions where superior quality of white light is required LUXEON CS HE CoBThis high-efficacy, square footprint version of the CS CoBs is easy design-in for new programs and is a cost-effective replacement for solutions where efficiency is paramount

LUXEON CS HE CoBThis high-efficacy, square footprint version of the CS CoBs is easy design-in for new programs and is a cost-effective replacement for solutions where efficiency is paramount LUXEON CX Plus CoB (Gen 2)Industry standard footprint. LES of 6, 9, 12, 14mm. CCT 2700K to 5000K and CRI or 80 and 90. Easy design-in.

LUXEON CX Plus CoB (Gen 2)Industry standard footprint. LES of 6, 9, 12, 14mm. CCT 2700K to 5000K and CRI or 80 and 90. Easy design-in.

LUXEON CX Plus CoB High DensityFlux, up to 5600 lm, an industry standard footprint of 13.35mm2, and LES of 4.5mm, 6mm, and 9mm. An effortless upgrade to higher flux and better value.

LUXEON CX Plus CoB High DensityFlux, up to 5600 lm, an industry standard footprint of 13.35mm2, and LES of 4.5mm, 6mm, and 9mm. An effortless upgrade to higher flux and better value.

LUXEON CX Plus CoB High Density (Below BBL)Impressive white color at 95CRI, 2- and 3-step MacAdam ellipse Below Black Body Line. Industry standard footprint of 13.35mm2, and LES of 4.5mm, 6mm, and 9mm.

LUXEON CX Plus CoB High Density (Below BBL)Impressive white color at 95CRI, 2- and 3-step MacAdam ellipse Below Black Body Line. Industry standard footprint of 13.35mm2, and LES of 4.5mm, 6mm, and 9mm. LUXEON CoB with CrispWhite TechnologyCrispWhite Technology delivers a natural crisp whiteness by activating Fluorescent Whitening Agents in paints and fabrics to boost attractiveness in retail shops.

LUXEON CoB with CrispWhite TechnologyCrispWhite Technology delivers a natural crisp whiteness by activating Fluorescent Whitening Agents in paints and fabrics to boost attractiveness in retail shops. LUXEON CoB with CrispColor TechnologySpecial phosphor technology creates a higher gamut color rendering than existing solutions. A specific color point be low the Black Body Line makes colors pop and fabrics come to life.

LUXEON CoB with CrispColor TechnologySpecial phosphor technology creates a higher gamut color rendering than existing solutions. A specific color point be low the Black Body Line makes colors pop and fabrics come to life. LUXEON CoB with CrispColor TechnologySpecial phosphor technology creates a higher gamut color rendering than existing solutions. A specific color point be low the Black Body Line makes colors pop and fabrics come to life.

LUXEON CoB with CrispColor TechnologySpecial phosphor technology creates a higher gamut color rendering than existing solutions. A specific color point be low the Black Body Line makes colors pop and fabrics come to life. LUXEON CoB with FreshFocus TechnologyFreshFocus Technology creates the most impactful lighting by accentuating the appeal of a variety of fresh food areas such as supermarkets, delis, butcher shops and bakeries.

LUXEON CoB with FreshFocus TechnologyFreshFocus Technology creates the most impactful lighting by accentuating the appeal of a variety of fresh food areas such as supermarkets, delis, butcher shops and bakeries.

LUXEON XR-5050 HE8, 12 or 16 LUXEON 5050 Square LEDs on a MCPCB substrate, with electrical connectors. Easier system integration, faster time to market, and use with industry standard optics.

LUXEON XR-5050 HE8, 12 or 16 LUXEON 5050 Square LEDs on a MCPCB substrate, with electrical connectors. Easier system integration, faster time to market, and use with industry standard optics. LUXEON XR-5050 Round

LUXEON XR-5050 Round LUXEON XR-5050 SQR8, 12 or 16 LUXEON 5050 Square LEDs on a MCPCB substrate, with electrical connectors. Easier system integration, faster time to market, and use with industry standard optics.

LUXEON XR-5050 SQR8, 12 or 16 LUXEON 5050 Square LEDs on a MCPCB substrate, with electrical connectors. Easier system integration, faster time to market, and use with industry standard optics. LUXEON XR-70704 LEDs on an MCPCB deliver more than 5000 lm at 170 lm/W. Eliminates LED-assembly engineering costs, tooling costs, and material inventory costs while accelerating time-to-market.

LUXEON XR-70704 LEDs on an MCPCB deliver more than 5000 lm at 170 lm/W. Eliminates LED-assembly engineering costs, tooling costs, and material inventory costs while accelerating time-to-market. LUXEON XR-HL2XStandard modules in 8-up, 12-up, and 16-up formats on MCPCB deliver more than 2800 lumens and 184 lm/W. Simplifies and speeds up luminaire design.

LUXEON XR-HL2XStandard modules in 8-up, 12-up, and 16-up formats on MCPCB deliver more than 2800 lumens and 184 lm/W. Simplifies and speeds up luminaire design.

Human Centric Lighting

LUXEON FusionA single platform for Dim-to-Warm, Color Tuning, and Full-Output White light. 1800K to 10000K, CRI>90 and micro color tuning in one SKU.

LUXEON FusionA single platform for Dim-to-Warm, Color Tuning, and Full-Output White light. 1800K to 10000K, CRI>90 and micro color tuning in one SKU.

LUXEON® SkyBlue™The simplest, most efficient circadian lighting LED solution. Deliver superior melanopic ratios at comfortable CCTs and minimize engineering costs.

LUXEON® SkyBlue™The simplest, most efficient circadian lighting LED solution. Deliver superior melanopic ratios at comfortable CCTs and minimize engineering costs. LUXEON 2835 Commercial Deep DimmingThe mid-power product with Deep Dimming capability ensures that your fixtures and installations remain uniform when dimming the current levels to 1% of the typical current or less.

LUXEON 2835 Commercial Deep DimmingThe mid-power product with Deep Dimming capability ensures that your fixtures and installations remain uniform when dimming the current levels to 1% of the typical current or less. LUXEON 3030 HE Plus Deep DimmingConsistent and uniform deep-dimming. 0.1 Vf width by default. Top lm/W performance, long lifetime, and pure 3 SDCM color bin.

LUXEON 3030 HE Plus Deep DimmingConsistent and uniform deep-dimming. 0.1 Vf width by default. Top lm/W performance, long lifetime, and pure 3 SDCM color bin.

LUXEON IR 2720 LineHigh-power IR at 850nm and 940nm. 1300mW of radiometric Power at 1000mA, Tj=25°C.

LUXEON IR 2720 LineHigh-power IR at 850nm and 940nm. 1300mW of radiometric Power at 1000mA, Tj=25°C. LUXEON IR Compact Line1.9mm x 1.37 IR package delivers 1050 mW at 850nm and 1150mW at 940nm.

LUXEON IR Compact Line1.9mm x 1.37 IR package delivers 1050 mW at 850nm and 1150mW at 940nm. LUXEON IR Domed Line3.7mm x 3.7mm domed package delivers 5 emission patterns 50°, 60°, 90°, 150°, and 95 x 58°. 1350mW @ 850nm and 1450mW @ 940nm.

LUXEON IR Domed Line3.7mm x 3.7mm domed package delivers 5 emission patterns 50°, 60°, 90°, 150°, and 95 x 58°. 1350mW @ 850nm and 1450mW @ 940nm. LUXEON IR Family for Automotive

LUXEON IR Family for Automotive LUXEON IR ONYXContinuous broadband infrared (IR) emission from 650 to 1100nm from a 2.75mm x 2.0mm package with 2 pad configuration.

LUXEON IR ONYXContinuous broadband infrared (IR) emission from 650 to 1100nm from a 2.75mm x 2.0mm package with 2 pad configuration. LUXEON UV FC LineUVA 380nm to 420nm from a 1.0mm2 CSP package with a maximum drive current of 1A/mm2 for superior flux and reduced LED count.

LUXEON UV FC LineUVA 380nm to 420nm from a 1.0mm2 CSP package with a maximum drive current of 1A/mm2 for superior flux and reduced LED count. LUXEON UV U LineUVA SMT LED features 200 micron spacing for high power density (W/cm²), superior efficiency, and design freedom.

LUXEON UV U LineUVA SMT LED features 200 micron spacing for high power density (W/cm²), superior efficiency, and design freedom.

LUXEON Display LEDsPurpose built LEDs optimized for display backlighting with leading lm/$ and lm/W

LUXEON Display LEDsPurpose built LEDs optimized for display backlighting with leading lm/$ and lm/W LUXEON Flash 9 FamilyThe clear choice for the bext possible images in a digital imaging platform

LUXEON Flash 9 FamilyThe clear choice for the bext possible images in a digital imaging platform LUXEON Flash 9X FamilyThe clear choice for the bext possible images in a digital imaging platform

LUXEON Flash 9X FamilyThe clear choice for the bext possible images in a digital imaging platform LUXEON Flash 7 FamilyThe clear choice for the bext possible images in a digital imaging platform

LUXEON Flash 7 FamilyThe clear choice for the bext possible images in a digital imaging platform LUXEON Flash V1 FamilyThe clear choice for the bext possible images in a digital imaging platform

LUXEON Flash V1 FamilyThe clear choice for the bext possible images in a digital imaging platform

LUXEON FX2LUXEON FX2 is an 1mm2 emitter available in 2-pad/3-pad layouts, and flux enhanced versions. Ideal LED for headlighting applications.

LUXEON FX2LUXEON FX2 is an 1mm2 emitter available in 2-pad/3-pad layouts, and flux enhanced versions. Ideal LED for headlighting applications. LUXEON NeoLUXEON Neo - 0.5mm2 product optimized for miniature size enabling high density advanced digital beam headlights.

LUXEON NeoLUXEON Neo - 0.5mm2 product optimized for miniature size enabling high density advanced digital beam headlights. LUXEON Altilon IntenseSingle die, 0.5mm2 emitter optimized for small source size to enable slim head lamps.

LUXEON Altilon IntenseSingle die, 0.5mm2 emitter optimized for small source size to enable slim head lamps. LUXEON Altilon SMDMulti-emitter family with the smallest form factors and ease of attachment to PCBs - for headlighting applications.

LUXEON Altilon SMDMulti-emitter family with the smallest form factors and ease of attachment to PCBs - for headlighting applications. LUXEON Altilon IntenseA family of 0.5mm2 multi-die products optimized for small source sizes to enable slim head lamps.

LUXEON Altilon IntenseA family of 0.5mm2 multi-die products optimized for small source sizes to enable slim head lamps. LUXEON GoStandard LED module with heat-sink for headlighting applications with small size, excellent thermals and precision alignments for optics.

LUXEON GoStandard LED module with heat-sink for headlighting applications with small size, excellent thermals and precision alignments for optics. LUXEON LxNRegulated LED bulbs made to last, using the latest LED technology and most durable components.

LUXEON LxNRegulated LED bulbs made to last, using the latest LED technology and most durable components. LUXEON MxNTurnkey integrated, high performance LED solutions for unique adaptive driving beam requirements.

LUXEON MxNTurnkey integrated, high performance LED solutions for unique adaptive driving beam requirements. LUXEON Altilon SMD PnPIntegrated L2 with multi-emitter solutions for ease of integration.

LUXEON Altilon SMD PnPIntegrated L2 with multi-emitter solutions for ease of integration. LUXEON Altilon TopContact PnPLeading integrated high power LED solution for front lighting applications.

LUXEON Altilon TopContact PnPLeading integrated high power LED solution for front lighting applications.

Single Die

Multi Die

LED Solutions & Modules

LUXEON FX2LUXEON FX2 is an 1mm2 emitter available in 2-pad/3-pad layouts, and flux enhanced versions. Ideal LED for headlighting applications.

LUXEON FX2LUXEON FX2 is an 1mm2 emitter available in 2-pad/3-pad layouts, and flux enhanced versions. Ideal LED for headlighting applications. LUXEON NeoLUXEON Neo - 0.5mm2 product optimized for miniature size enabling high density advanced digital beam headlights.

LUXEON NeoLUXEON Neo - 0.5mm2 product optimized for miniature size enabling high density advanced digital beam headlights. LUXEON Versat 2020 LineSmallest auto-grade emitter avaiable in CW, PCA, Amber and Reds.

LUXEON Versat 2020 LineSmallest auto-grade emitter avaiable in CW, PCA, Amber and Reds. LUXEON Versat 3030 LineIndustry standard emitter available in CW, PCA, Red, Amber, and PC Green.

LUXEON Versat 3030 LineIndustry standard emitter available in CW, PCA, Red, Amber, and PC Green. LUXEON Altilon SMD DTIndustry-leading dual color SMD solutions for daytime running and front turn lamps

LUXEON Altilon SMD DTIndustry-leading dual color SMD solutions for daytime running and front turn lamps LUXEON Versat Dual ColorSingle source, dual color LED product family designed for combined front turn and DRL automotive signaling applications

LUXEON Versat Dual ColorSingle source, dual color LED product family designed for combined front turn and DRL automotive signaling applications LUXEON LxNRegulated LED bulbs made to last, using the latest LED technology and most durable components.

LUXEON LxNRegulated LED bulbs made to last, using the latest LED technology and most durable components. LUXEON 3D LEDLUXEON 3D LED helps you bring to life the versatile shapes of your 3D lighting design for all exterior signaling and styling functions.

LUXEON 3D LEDLUXEON 3D LED helps you bring to life the versatile shapes of your 3D lighting design for all exterior signaling and styling functions.

LED Solutions & Modules

LUXEON Versat 2020 LineSmallest auto-grade emitter available in CW, PCA, Amber and Reds.

LUXEON Versat 2020 LineSmallest auto-grade emitter available in CW, PCA, Amber and Reds. LUXEON Versat 3030 LineIndustry standard emitter available in CW, PCA, Red, Amber, and PC Green.

LUXEON Versat 3030 LineIndustry standard emitter available in CW, PCA, Red, Amber, and PC Green. SignalSureLow to Mid Power LED in an industry standard footprint for rear signaling

SignalSureLow to Mid Power LED in an industry standard footprint for rear signaling LUXEON LxNRegulated LED bulbs made to last, using the latest LED technology and most durable components.

LUXEON LxNRegulated LED bulbs made to last, using the latest LED technology and most durable components. LUXEON 3D LEDLUXEON 3D LED helps you bring to life the versatile shapes of your 3D lighting design for all exterior signaling and styling functions.

LUXEON 3D LEDLUXEON 3D LED helps you bring to life the versatile shapes of your 3D lighting design for all exterior signaling and styling functions.

LED Solutions

LUXEON 3D LEDLUXEON 3D LED helps you bring to life the versatile shapes of your 3D lighting design for all exterior signaling and styling functions.

LUXEON 3D LEDLUXEON 3D LED helps you bring to life the versatile shapes of your 3D lighting design for all exterior signaling and styling functions.

LUXEON IR Domed for Automotive LineHigh power infrared emitters with engineered primary optics for high efficiency and beam control

LUXEON IR Domed for Automotive LineHigh power infrared emitters with engineered primary optics for high efficiency and beam control

LED Technology

Exclusive technology at every level of LED manufacturing enables LUXEON illumination grade LED light engines.

Spotlight

NightScape Technology

NightScape Technology

NightScape Technology preserves the well-being of animals, plants, and people, reduces light pollution, and supports dark sky initiatives.

Learn more about NightScape Technology >CoB Technology

Understanding CoB Technology

CoBs are an essential LED format that enable highly efficient and very high quality light in many indoor and outdoor applications.

CoB LED Technology >

Lumileds CoB Finder

Lumileds offers thousands of LUXEON CoB options for LES, CRI, CCT, light output, light spectra, and more. Our LUXEON CoB Finder makes it easy to find the product you need.

CoB Product Finder >Video Library

See all videos >Document Library

Design resources

Design files

Design Tools

Calculators and online resources for: optical, thermal, mechanical and electrical components.

Login »